We appear to be in a show room passage. With a tree-sawn grid-nailed floor. Level, horizontal …

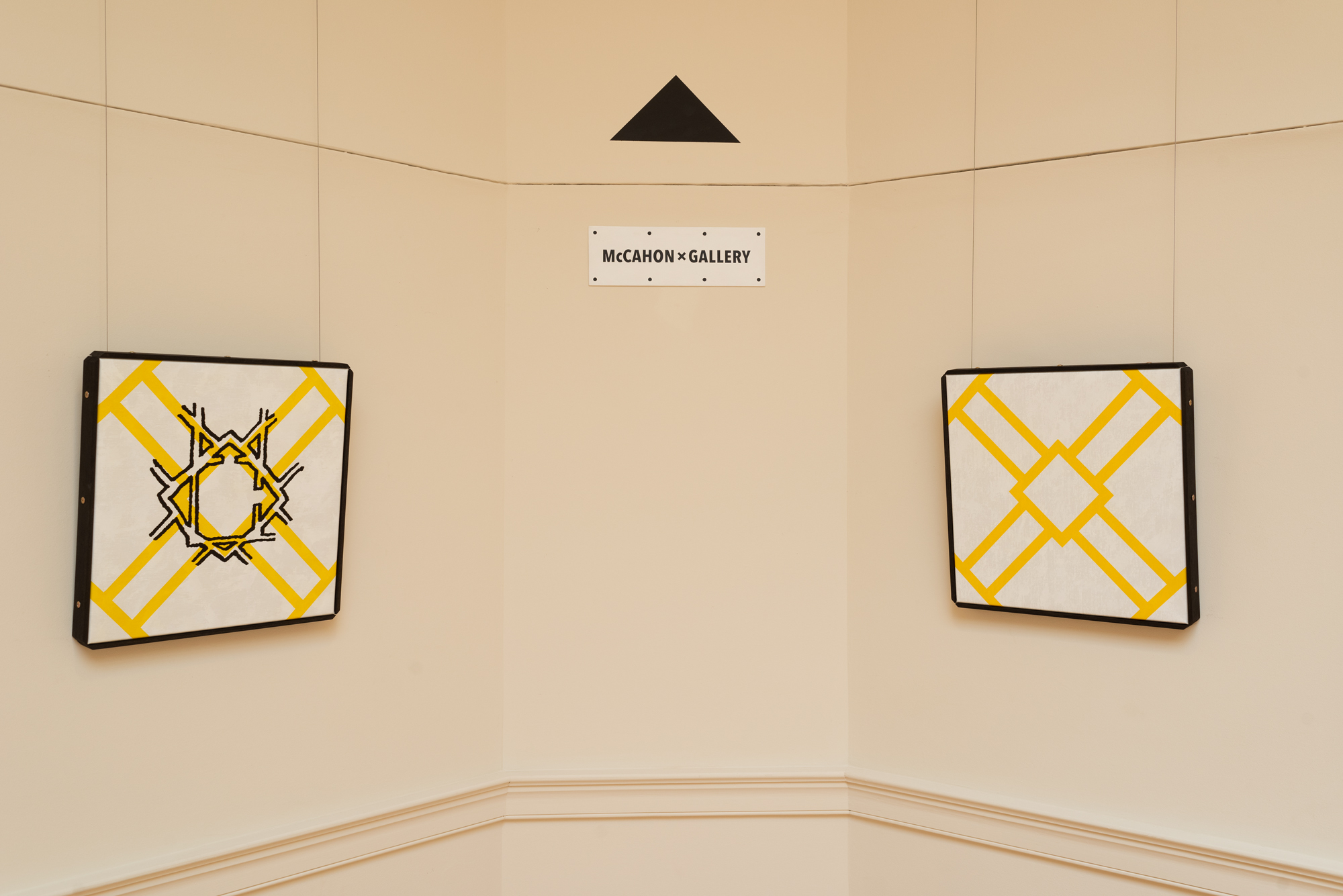

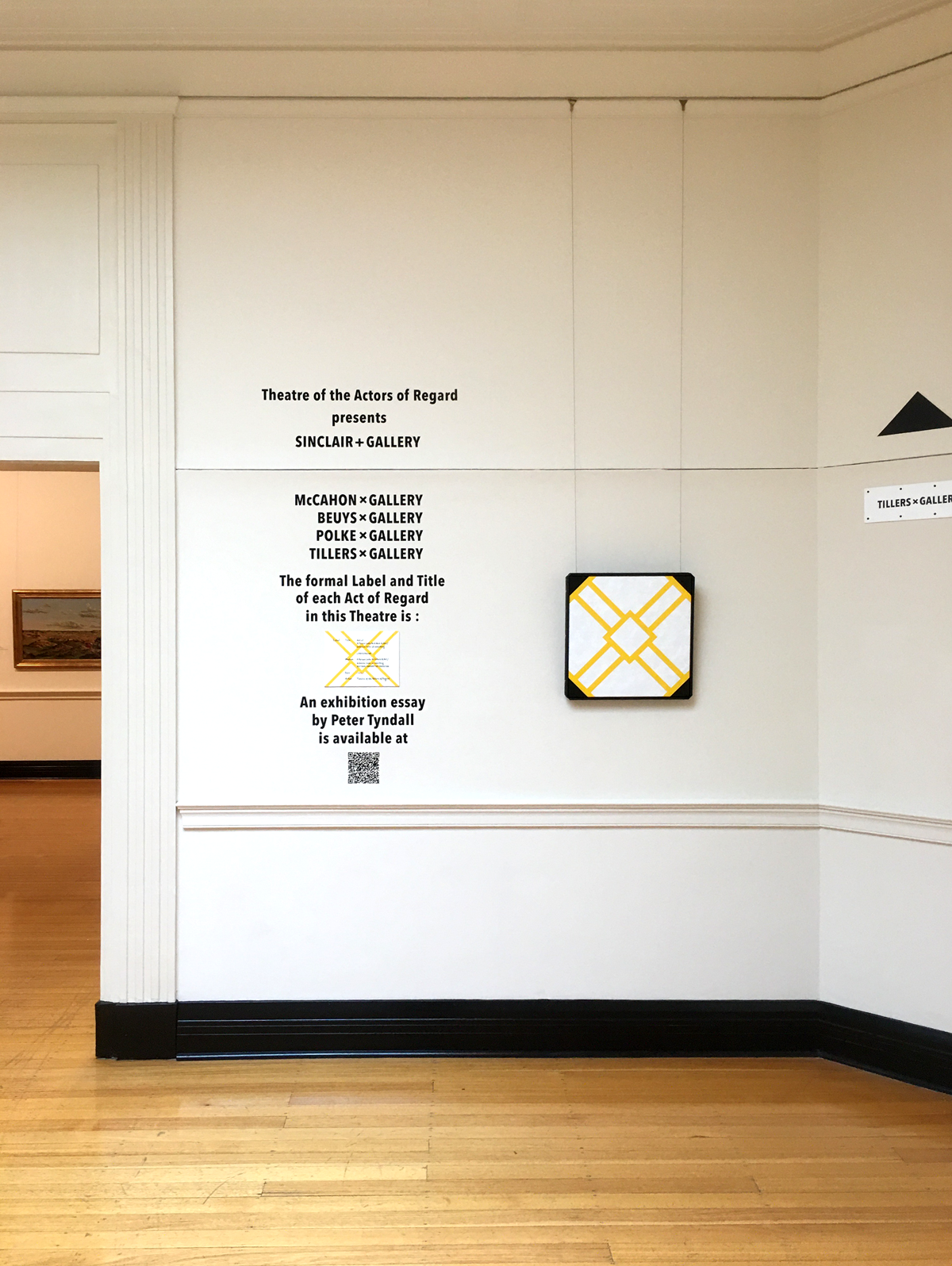

Sigmar Polke, Imants Tillers, Joseph Beuys and Colin McCahon are the cardinal points. Named on the interior cut-corner walls and echoing the crown nameplate of the Sinclair Gallery, which itself fits neatly inside the Castlemaine Art Gallery and Museum (recently renamed Castlemaine Art Museum), the current exhibition SINCLAIR+GALLERY by Peter Tyndall, the Hepburn Springs-based artist, is a vertiginous reflection on the installation of artwork in the storied gallery of the museum. At its centre, there is a plinth that inverts the octagonal structure of the gallery and features a kitchen instrument that miniaturises and points to the gridded light-well of the ceiling. On the gallery walls, the picture rail mouldings help to reveal Tyndall’s elegant iconography, which is repeated in the paintings that are framed and hung below.

Meta-painting may seem an apt signifier for Tyndall’s concept-driven process, but perhaps today that more readily signifies Facebook’s online algorithmics. Opposed to aesthetic projects like Tyndall’s, these social media companies have co-opted and monetised the (visual) search function ruthlessly for nearly two decades. Network painting, perhaps? No. But walking through an art deco building that opened in 1931, it’s impossible not to connect this enduring outcome of an Australian modernism with the indifferent digital aesthetics of the information age. (The grid of the QR code and its repetition in laminated Victorian Government signage at every entrance are only the most obvious examples of this.) In 1913, Elsie Barlow, a founding member of the Twenty Melbourne Painters Society, proposed the creation of a permanent art gallery for Castlemaine. The present gallery building ended up being designed by architect Percy Meldrum, who had earlier travelled to Chicago and was a Frank Lloyd Wright acolyte. Upon his return to Melbourne, Meldrum partnered with Arthur George Stephenson, whom he had met in London at the Architectural Association after the war effort, becoming a pioneer of architectural modernism in the provinces of the interwar colony.

Tyndall’s exhibition calls us back to this opening. It is immediately clear that it is the architecture that is the fundamental feature of Tyndall’s conceptual concerns for SINCLAIR+GALLERY (architecture was indeed his first discipline). Curated by Jenny Long, the entire space has been activated as a kind of modernist crypt. Unofficially it commemorates the 50th anniversary of Tyndall’s first art exhibition. Here, Boris Groys might declare SINCLAIR+GALLERY an “asymmetrical war” between the artist and his artwork. Accompanying the exhibition and boldly pronounced upon one wall, there is the QR link to Peter Tyndall artist book. Tyndall is now in his seventies and a master of a distinctly Australian conceptualism that acknowledges its own provincialism by distancing and anonymising the work from the viewer—-the repetitive “someone” (you) who looks at a work of art, in the “Theatre of the Actors of Regard (TAR)”. What is Tyndall trying to show us, exactly? We, the humble public, the visitors from outta town?

Tyndall’s work appears in Castlemaine—-he was born and raised in goldfields Victoria—-in a way that makes clearer his intentions and in ways that it doesn’t quite when I’ve seen it displayed in the commercial spaces of Anna Schwartz Gallery, or even in the unmoored, twenty-first century “global city” internationalism of Melbourne’s or Sydney’s public collections. Spiritually his work is anchored by way of his consistent reference to the Fosterville Institute of Applied and Progressive Cultural Experience (FIAPCE). Google Maps shows me a town near Bendigo, a school that was closed in 1953 and a goldmine that was opened in 2005.

Speaking to the Midland Express, Tyndall explains that “the installation celebrates the interconnectedness of all things—-the sky and the earth and everything in between”. On the Castlemaine Art Museum’s website, Doug Hall’s reflection on his fifty-year friendship with the artist emphasises his “curiosity and not knowing”. The regional setting, the historical intervention, coupled with dedications to the coterie of artist-influences unafraid of using diagonal lozenges in their work, makes the visit to Castlemaine richly intriguing, disorienting initially for its historical avant-gardism as much as for its gesture to Tyndall’s nascent interest in Zen Buddhism.

Its coherence comes at the centre of the exhibition where a second, miniature exhibition is colloquially titled “the potato and the sky”, in which an Economic Potato Chipper is mounted, guillotine-like, onto the white “corner-cut pedestal”. The sky is the overhead grid of the gallery light well. The link between the potato chipper and the art deco location is confounding. Obviously, the grid-structure that appears in both links the two in form alone. I think of the first part of Patrick White’s final collection of short stories, Three Uneasy Pieces (1987), ‘The Screaming Potato’:

Prayer and vegies ought to help towards atonement. But don’t.

Oh lord, dispel our dreams, of murders we did not commit—-or did we?

Fascinated by the grid of the chipper, Tyndall presents the device here in its mass industrial glory. It’s less Bauhaus and more Our House. When Tyndall’s brother, Philip, produced a film portrait of the writer Gerald Murnane, Words and Silk (1990), the literary formalism of Murnane’s tightly worked sentences and strict set of topics (horseracing, landscape, memory) reflected also on Peter’s asceticism, to my mind. Fellow Memo writer, Vicki Perin previously made this connection, noting Tyndall’s strange portrait of Murnane, posted online as a gif image.

I have just finished reading Christos Tsiolkas’s Dead Europe (2005), and so I am inclined to read Tyndall’s (self)mythologising against the grain, formally speaking. Tsiolkas’ novel tells the story of a young Greek-Australian photographer who returns to Europe, looking to understand his family’s migration to Melbourne long after his father’s untimely death. What he encounters, however, leads to his chaotic backslide through a fractured and divided landscape—Europe—and upon returning to Melbourne, he is quite literally transformed into a vampire. I am tempted to see Tyndall’s meditation on the grid-form and “hanging canvas” motif as a talisman to ward off this kind of bad omen from the distanced perspective of the colony.

We might also see something of an inversion of the logic for painting discovered by Frank Stella in the 1960s. His repetition of the painting’s frame in lines of paint is turned around by Tyndall, and the external pressure placed on the wall-hung object in his work recalls the minimalist activation of the location in which the artwork is present along with the additional presence of its viewer (the someone, you). Onto this can be projected any number of lucky charms, notes or observations that get caught in the grid. This is where Tyndall’s obsession with culture—as a part of “the art cult”—gets most exciting, I feel.

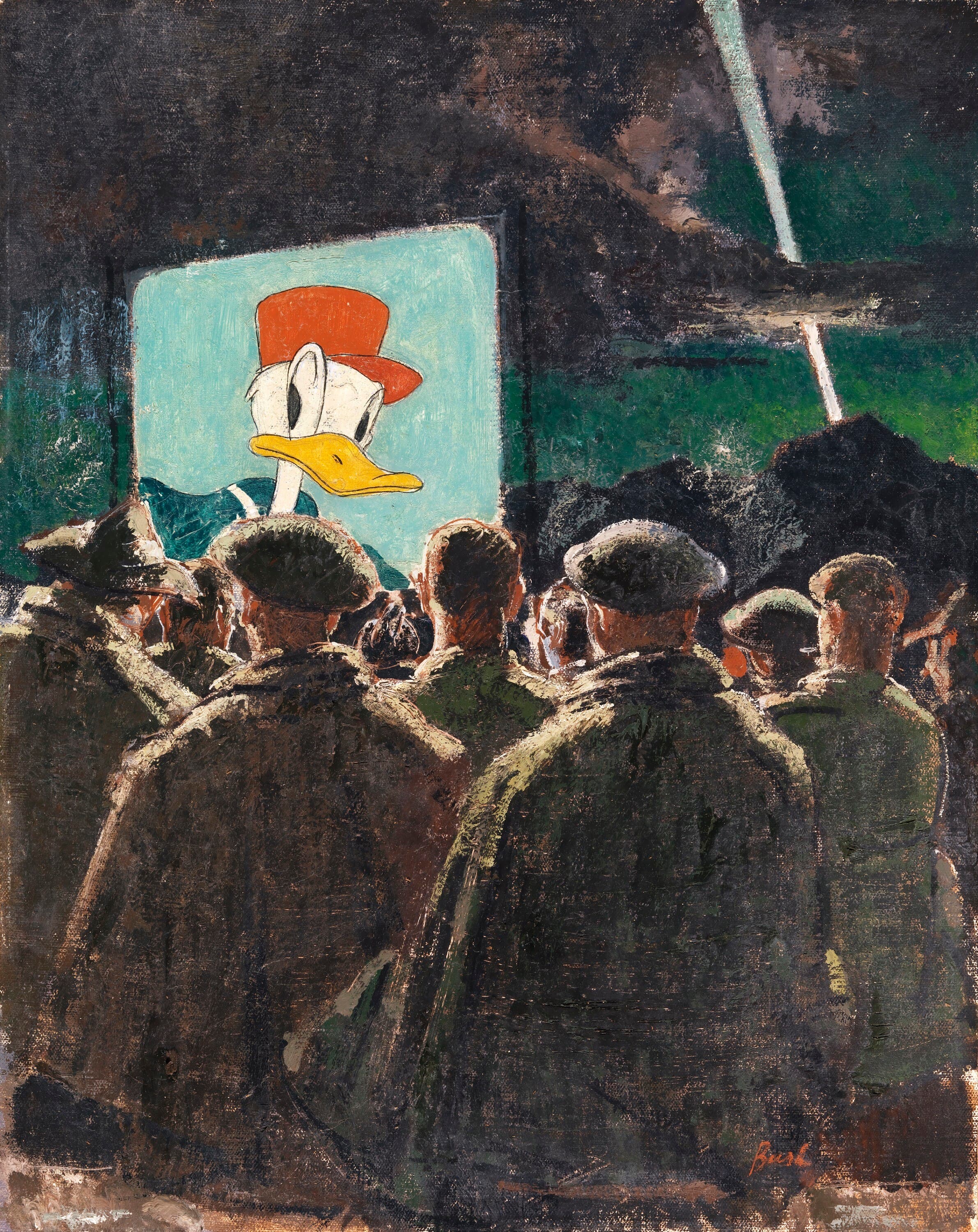

David Bowie’s last album, ★ (Blackstar), almost inexplicably features in the digital room sheet for the show, while Ron Weasley’s pre-Quidditch breakfast is screen-grabbed (yes, Harry Potter), Stanley Kramer’s film It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, World (1963) has had its promotional poster edited and reposted and a catalogue image of a Columbian Emerald, Onyx and Diamond corner brooch from a recent Leonard Joel auction catalogue appears as satellite or incidental imagery for the exhibition on Tyndall’s blogos.haha.blogspot.com (7 November and 16 December 2021 and 16 February 2022, respectively). The lure is the tiny lozenge shape that appears on the brass Sinclair Gallery nameplate, between the two words. The + in Tyndall’s title reveals the additional logic that this tiny feature apparently allows. Its four diagonal sides help to break the room into its cardinal points: Tillers, Polke, Beuys, McCahon. There is no hierarchy, they are simply coterminous point on the continuous plain, creating the opening for the field in which the exhibition operates. Tyndall makes it clear their emphasis on what to do with corners is what justifies their appearance in the essay accompanying the exhibition.

The cut corners, then, are an entry point into the chicanery of an endless language game, but a language that is inspired by formulas and could also have been dedicated to the artistic legacy of Joseph Kosuth.

The SINCLAIR+GALLERY is named in honour of Beth Sinclair (1919-2014), director of the Castlemaine Art Museum and Historical Museum from 1962-1975, and the first female public Art Gallery Director in Australia.

Given this week’s festive calendar-event timing for the annual International Women’s Day (IWD), it seems a fitting observation for an original girlboss. Tyndall goes much further, however. Clair means light and the prefix “Sin” is here interpolated by Tyndall to mean “Saint”. The Sinclairs, an Anglo-Saxon naming group, is postulated as originating as far back as the ninth century in the increasingly mad (insane?) liner notes to the show. The PDF document linked via another infernal QR code on the gallery wall is long and seen in full looks like a digital noodle. Even Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code (2003) rates a mention.

As I exit the crypt, I land on the phrase: “minimum chips and two potato cakes, please”. The entire exhibit is signed “Peter Tyndall Bonzaview December 2021”. I think of a favourite local band called Minimum Chips. One of their better tunes played itself back in my head as I stepped out onto Lyttleton Street.

Giles Fielke is a lecturer at Monash University and an editor of Memo Review.